The integration of African, Arab, Persian, Indian, and European influences has led to the formation of a unique and vibrant Swahili culture. Spanning from the coast of Somalia through Kenya, Tanzania, and into Mozambique, the Swahili culture draws from a rich history that goes back over a thousand years. The Kenyan coastal region, in particular, reflects this multicultural synthesis due to its geographical location, which has historically positioned it as a hub for trade and cultural exchanges.

The Origins and Influence of Swahili Culture

The Swahili culture’s development can largely be traced back to interactions fostered by trade. Ancient trade routes across the Indian Ocean facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices. Traders from the Middle East, Persia, India, and later Europe, were drawn to the Swahili coast, bringing with them goods like spices, textiles, and ceramics. In return, they took African goods such as gold, ivory, and timber back to their homelands. This international commerce nurtured not just economic prosperity, but also a cosmopolitan cultural landscape unparalleled in its diversity.

Language and Communication

Kiswahili, the language spoken along the Swahili coast, is a Bantu language deeply influenced by external interactions. While it forms the backbone for communication among coastal communities, Kiswahili also incorporates a wealth of loanwords from various tongues that engaged in trade along the coast. Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, and English each contributed to its lexicon, making it a rich tapestry of linguistic borrowing.

For example, the Arabic influence is profound not only in vocabulary but also in the script originally used to write the language. The coastal trade relationships necessitated a common language, and Kiswahili flourished as this *lingua franca*. The language now extends beyond the coast, serving as a national language in Kenya and Tanzania, and an official language of the African Union, emphasizing its role in uniting diverse peoples. Those interested in exploring the complicated yet beautiful evolution of Kiswahili can find a wealth of articles and resources online that delve into its history and current use.

Architecture and Urban Planning

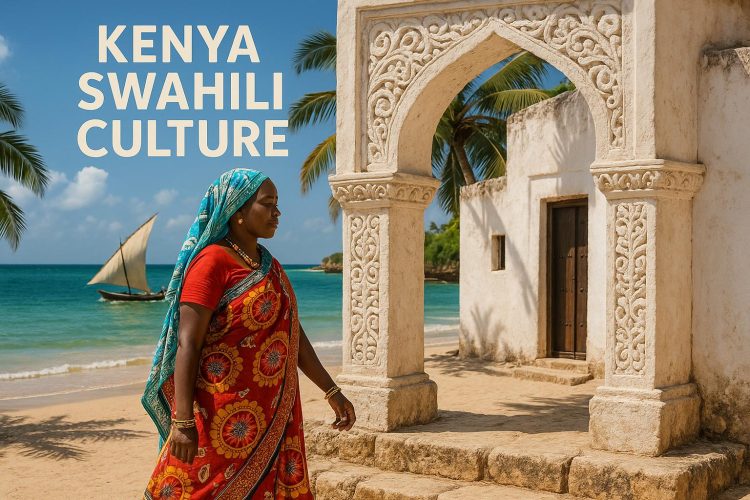

The architectural landscape of the Swahili coast is as distinct as its people. Towns like Mombasa, Lamu, and Malindi house coral stone buildings, a staple of the traditional Swahili architectural style. These constructions are characterized by their solid stone structures, with walls crafted from coral rock and lime, offering durability against the coastal climate.

Another distinctive feature is the Swahili door, often made of hardwood and adorned with intricate carvings that present geometric patterns and floral motifs. These details serve not merely for aesthetic appeal but also signal the cultural influences – resonating with both local artistry and Islamic artistic traditions brought by Arab traders.

Swahili urban planning typically features narrow, winding streets, a design purposefully created to ensure shade from intense tropical sunlight and to facilitate cool breezes from the ocean. Throughout these coastal towns, you’ll find numerous mosques that highlight the community’s spiritual life. Serving as social and religious centers, these mosques are often architecturally impressive, with unique minarets rising above the settlements.

Cuisine and Culinary Traditions

The culinary traditions of the Swahili coast encapsulate its multicultural essence. Staples of Swahili cuisine, such as *pilau* and *biryani*, underscore Persian and Indian gastronomic influences. These dishes are distinguished by their complex spice blends, including cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, and cumin, resulting in a depth of flavor and an aromatic dining experience.

Coconut milk is a cornerstone of Swahili cooking, especially prevalent in curries, stews, and desserts, mirroring the influence of the tropical environment on local culinary practices. This ingredient showcases a harmonious blend of tropical agricultural practices with imported culinary customs.

Seafood forms another crucial aspect of the Swahili culinary identity. Given the proximity to the ocean, fish, prawns, and squid are often freshly prepared and cooked with local spices, blending both indigenous and foreign flavors. Additionally, Swahili cuisine includes a variety of fruits like mangoes, bananas, and pawpaw, commonly enjoyed fresh or in desserts.

Festivals and Social Practices

The social fabric of the Swahili coast is enriched by a tapestry of festivals and communal traditions, which are celebrated with great enthusiasm. Central to these celebrations is the *Maulidi festival*, held in Lamu to commemorate the birth of Prophet Muhammad. An event that draws people from different regions, it features religious processions, poetic recitations, and music. Festivals such as these provide a glimpse into the way the Swahili people maintain cultural interconnectedness and community bonds.

Music plays an integral role in Swahili cultural celebrations. One popular musical genre is *tarab*, which blends African rhythms with melodies from Arab and Indian music, often incorporating instruments like the oud and percussion drums. In social gatherings and ceremonies, this music becomes a means of storytelling and preserving the oral traditions that carry collective histories and values.

For those interested in exploring more about the Swahili coast’s distinctive cultural heritage, various academic publications, documentaries, and studies are available online. These resources delve into the complex yet fascinating history of the Swahili coast, shedding light on its dynamic cultural exchanges and enduring legacy.